Aesthetic Realism

The goal of this brief note is to sketch a modest form of aesthetic realism. In particular, I want to defend that at least some aesthetic properties are objective or, to be more precise, that some aesthetic predicates have non-subject-dependent extensions. As example, I will work with the predicate “tasty” (and its antonym “disgusting”) to argue that its extension is fixed by an objective property: flavour. In other words, when we say of something that it is tasty, we are not saying how it tastes to us, but just how it tastes period.

The structure is as follows. First I will sketch the phenomenon of using subjective, perspectival or context-dependent language for talking of objective, non-perspectival and/or context-invariant properties. I will present first the abstract general account and then illustrate it with the expression “to the left”. This is a perspectival expression, we use to talk about a non-perspectival property of objects: their location. Then, I will argue that we have good reasons to think that “tasty” works the same, it is a subjective expression we use to talk about an objective property of stuff: its flavor.

The basic idea is to rescue what I take to be a commonsensical intuition regarding the relation between “tasty” and flavor: that two things cannot be one tasty, the other not, and yet both taste the same.

Possible criticism:

My answer:

Still, the subjectivist might insist that flavor just is how stuff tastes, and of course, without someone to taste stuff, stuff would not taste at all. But I find this way of conceiving of flavor is wrongheaded, for it is based on a confusion between what is perceived with how it is perceived. To taste is to perceive flavor, but that does not mean that flavor just pops into existence when it is tasted, i.e.. when it is perceived. Idealism cannot be the default position when talking of perception.

The structure is as follows. First I will sketch the phenomenon of using subjective, perspectival or context-dependent language for talking of objective, non-perspectival and/or context-invariant properties. I will present first the abstract general account and then illustrate it with the expression “to the left”. This is a perspectival expression, we use to talk about a non-perspectival property of objects: their location. Then, I will argue that we have good reasons to think that “tasty” works the same, it is a subjective expression we use to talk about an objective property of stuff: its flavor.

The basic idea is to rescue what I take to be a commonsensical intuition regarding the relation between “tasty” and flavor: that two things cannot be one tasty, the other not, and yet both taste the same.

I. Context-sensitive expressions that do not express context-sensitive properties.

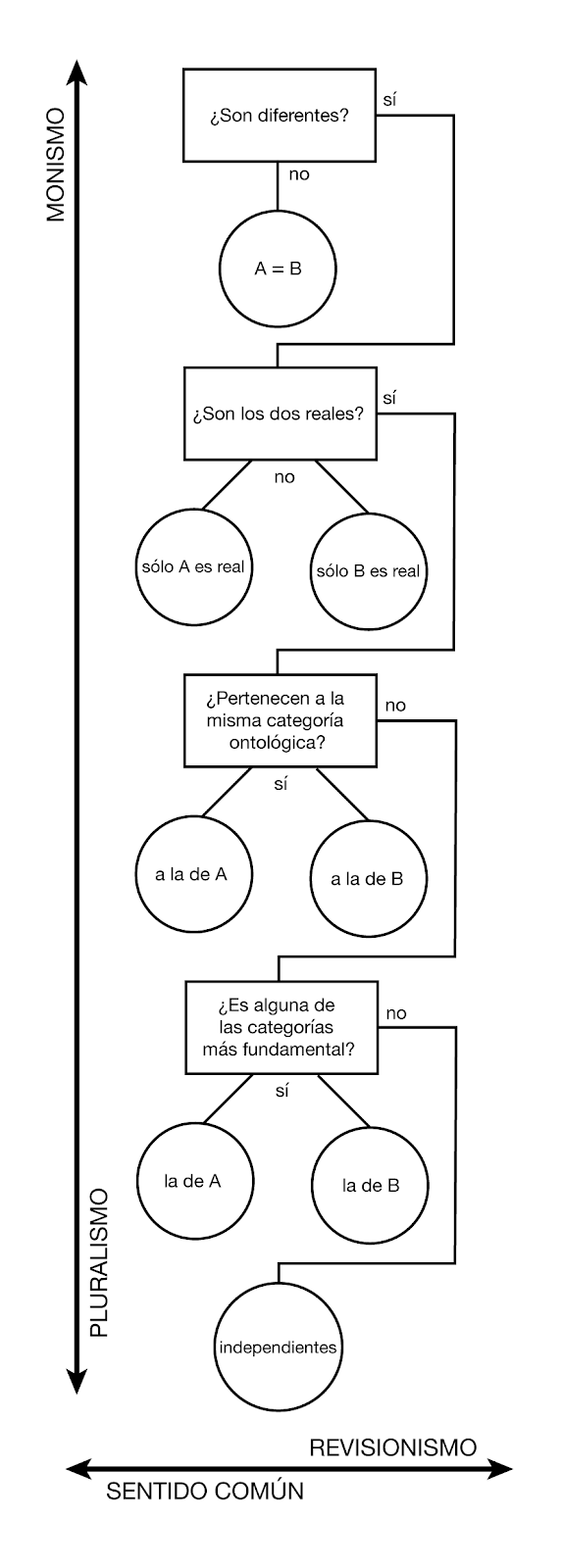

Whenever there are predicates P1 and P2 (and sometimes P3, P4, etc.) such that there is a (determinable) property P, at least one object X and a pair of contexts C1 and C2 such that:

Part I: Shiftiness

1. In context C1, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is P1” is true.

2. In context C2, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is P2” is true.

3. P1 and P2 are incompatible predicates (nothing can be both P1 and P2 at the same time).

Part II: Stability

4. Both “X is P1” and “X is P2” are adequate answers to the question “How P is X?” (or similar: “What is the P of X?”, “Which P is X?”, “How does X P?”, etc. Remember that P is a determinable property).

5. Yet changing X from C1 to C2 does not change how P X is.

Or another way of testing for stability:

5’. For every X and Y, if X and Y are of the same P (i.e., the P of X = the P of Y), then X is P1 iff Y is P1, and X is P2 iff X is P2.

Then, P1 and P2 (which are context-sensitive) express property P (which is not context-sensitve).

The most obvious examples of pairs of predicates like this are “to the left” and “to the right”. Right now, the window of my studio is to the right, but if I turn around it would be to the left. Being to the right and being to the left are incompatible. Both are acceptable answers to the question “Where is the window?’, yet my turning around does not change where the window is. It is not the window that moves, it is myself, i.e. it is the aspects of the context that the expressions “to the left” and “to the right”. Thus, even though being to the left of Axel Arturo Barceló at 2:06 pm on Saturday the 7th of January 2012, ... may well be an actual genuine (relational) property of the window, the window having that property is not what makes true the proposition expressed by me when I (literally, non-descriptively, de re, etc.) assert that "the window is to the left".

Predicates like this, i.e., predicates that are both shifty and stable do not actually denote any genuine property. Instead, they are context sensitive expressions we use to talk about genuine properties. In this example, there are no such properties as being to the left or being to the right; instead, “to the left” and “to the right” are context-sensitive expressions we use to talk about the window’s location. The window’s location is one of its genuine properties; and it is its having this property is what makes the propositions expressed by “X is P1” in C1 and “X is P2” in C2 true, not it being spatially related in some particular way to the utterer in each context. Consequently, the truth of these assertions is still an objective affair.

Other examples of adjectives P1 and P2 are: gradual antonyms like “tall” and “short” (for P=height), color adjectives like “green, with no touch of blue” and “green, with a touch of blue” (for P=color), etc.

This means that adjectives like P1 and P2 do not correspond to genuine properties, but instead are context-relative ways of talking about real properties, and their extensions are real properties as well (determinates of the determimable P). There are no such properties as being tall or short. Instead “tall” and “short” are context-sensitive expressions we use to talk about height, i.e., about how tall people are. People’s heights, in contrast, are genuine properties. Also, there are no blue and green. Instead, “blue” and “green” are context-sensitive expressions we use to talk about the color of things. This does not mean, however, that these colors we talk about are not genuine, objective properties or that they are not the kind of properties we ascribe to objects when we say they are green or blue. They are. It just means that different uses of the adjective “blue” may pick different properties – different colors – in different contexts. There is no such thing as the color that every thing we might truly call “blue” in some context has.

In a recent draft paper, Mario Gómez-Torrente (2014) also makes the point that, even though the predicates P1, P2, P3, etc. we might use to talk about these properties (color, location, height, etc.) may be more or less vague, more or less precise, etc., these features do not translate to the properties themselves. Colors are neither coarse nor fine grained, it is the way we talk about them which might be more or less fine or coarse grained.

A. First Unnecessary Intermezzo : Epistemology

[This has nothing to do with aesthetic realism, so skip if you want to]

What I find interesting is that similar puzzles arise with respect to other sorts of predicates, for example, “knowing that s” and “not knowing that s” for (P=knowing about s). I think this means that there is no genuine property corresponding to these predicates, i.e. there is no such property as, for example, knowing the way to San José. Instead, they are context sensitive expressions we use to talk about what we know about the world. What we know about the world, on the other hand, is a genuine property of us. Consequently, somebody's knowledge of the world (or his knwoledge-base, as it is also commonly known) is a property just like an object's color. It is neither fine nor coarse grained. It is our description of this property that can be fine or coarse grained.

But notice that when I say that someone's knowledge of the word is just like an object's color, i.e. a property. I do not mean that there is one property having knowledge about the world that everyone that has some knowledge of the world has, just like saying that an object's color is one of its properties does not mean that there is just one property having color that every colored object has. Instead it means that whatever knowledge one has of the world that knowledge is a property of that agent, just like whatever color an object has is a property of that object. Just like different objects can be of different colors, different agents can have different knowledge of the world. Thus, a predicate like "knows that Ernesto Zedillo is a criminal" is a contextually sensitive predicate we use to talk about what people know, just like the predicate "is light green, almost white" is a contextually sensitive predicate we use to talk about what color objects are. So you are right: objects have determinate properties, and either (i) there are no predicable properties because every time we seem to predicate a predicable property what makes the corresponding proposition true is just the object having its determinate property or (ii) they are disjunctive properties. When I talk of colors, the only genuine or basic properties are the determinate colors objects are. When I talk of knowledge, the only genuine properties are the determinate knowledge bases the agents have.

II. Aesthetic Realism

What I want to discuss now is whether the same issue arises in the case of predicates like “tasty” and “disgusting” (for P=flavor):

Part I: Shiftiness

There seem to be contexts C1 and C2 where

1. In context C1, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is tasty” is true.

2. In context C2, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is disgusting” is true.

3. tasty and disgusting are incompatible predicates (nothing can be both tasty and disgusting at the same time).

3. tasty and disgusting are incompatible predicates (nothing can be both tasty and disgusting at the same time).

Part II: Stability

4. Both “X is tasty” and “X is disgusting” are adequate answers to the question “How does X taste?”

5. Yet changing X from C1 to C2 does not change how X tastes.

Furthermore:

5’. For every X and Y, if X and Y taste the same, then X is tasty (in a given context C) iff Y is tasty (in the same context C), and X is disgusting (in a given context C) iff X is disgusting (in the same context C).

Notice that shiftiness is nothing but the anti-realist intuition that the same stuff can be tasty to some, but not to others, or to the same person in different moments and/or circumstances.

On the other hand, stability is nothing but the fact that whenever one finds something disgusting, if, instead of that thing, one had tasted something else that tasted the same, one would have found it disgusting as well. Furthermore, this is analogous to the fact that whenever one finds something to one’s left, if instead of that thing, one had found something else in that very same location, one would have found it one one’s left too. (Thus, my proposal aims to bring both intuitions together in a realist account that, nonetheless, captures the anti-realist intuition.)

This seems to me to be enough to say that there is no such property as tastiness, but that instead “tasty” and “disgusting” are just context sensitive expressions we use to talk about flavor.

What other aesthetic predicates are also shifty and stable, and so can we say to have objective extensions? I am not sure. Some, like “Salty” seem to be: On the one hand, they are clearly shifty. The same dish can be salty for one palate, and not salty for another. They are also stable, since the answer “It is salty” is appropriate to the question “how does it taste”, and yet when tasted by different palates, the dish does not change in taste. But others, like gorgeous do not seem to be: they are clearly shifty, but I am not sure if they are stable.

B. Second Unnecessary Intermezzo : Direct Reference in Predicates

[This has nothing to do with aesthetic realism, so skip if you want to]

Notice that everything I have said so far works for names (i.e., referring expressions) as well as for predicates. There are context sensitive names such that:

I. Shiftiness

1. In context C1, an utterance of “X is N1” is true.

2. In context C2, an utterance of “X is N2” is true.

3. N1 and N2 are incompatible names (nothing can be both N1 and N2 at the same time).

II. Stability

4. Both “X is N1” and “X is N2” are adequate answers to the question “Who/What is X?”.

5. Yet changing X from C1 to C2 does not change who or what X is.

1 to 5 are true if and only if N1 or N2 are context-sensitive expressions we use to talk about objects.

Furthermore, this test for context-sensitivity works is very similar to Kripke’s original puzzle motivating the distinction between directly referential terms and quantificational /descriptive nominals:

I. Shiftiness

1. In world W1, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is N1” is true.

2. In world W2, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is N2” is true.

3. N1 and N2 are incompatible predicates (nothing can be both N1 and N2 at the same time).

II. Stability

II. Stability

4. Both “X is N1” and “X is N2” are adequate answers to the question “ Who/What is X?”

5. Yet changing X from W1 to W2 does not change who or what X is.

1 to 5 are true if and only if N1 or N2 are descriptive names, not directly referential.

Thus, there might be a similar distinction at the level of predicates, i.e., we can talk of predicates that are descriptive of their extensions, and those that have their extensions directly:

Predicates P1 and P2 (and sometimes P3, P4, etc.) are descriptive for a property P, iff there is at least one object X and a pair of possible worlds W1 and W2 such that:

I: Shiftiness

1. In world W1, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is P1” is true.

2. In world W2, a (literal, assertoric, non-descriptive, de re, etc.) utterance of “X is P2” is true.

3. P1 and P2 are incompatible predicates (nothing can be both P1 and P2 at the same time).

II: Stability

3. P1 and P2 are incompatible predicates (nothing can be both P1 and P2 at the same time).

II: Stability

4. Both “X is P1” and “X is P2” are adequate answers to the question “How P is X?” (or similar: “What is the P of X?”, “Which P is X?”, “How does X P?”, etc.).

5. Yet changing X from W1 to W2 does not change how/what/which P X is.

Following the example above, predicates “to the east of Harlem” and “to the west of Harlem” are descriptive with respect to a place’s location in this sense. In worlds where Harlem is in different locations, some other entity X can be to the east of Harlem in one possible world, and to its west in another without actually changing location.

Now, my worry is how much of what we said about context sensitive predicates can we extend to these other predicates. In particular, are the propositions expressed by “X is P1” and “X is P2” made true by X having property P or do we also have to add to our ontology new properties for P1 and P2? Can we say that what makes true the proposition expressed by, for example, “Morningside Heights is west of Harlem” in our current world is just the fact that Morningside Heights has the location it has (or some other spatial property independent of where Harlem is) or is it instead that Harlem and Morningside Heights are so spatially located that the later is to the west of the former?

It seems to me, also, that in these cases, we must say that P1 and P2 are not directly predicative but descriptively so, i.e. they do not only contribute a property to the proposition expressed by their utterance, but instead contribute a description of such property.

III. Possible Caveats

Possible criticism:

But flavor is not objective either, so it does not matter that you have reduced tastiness to flavor, since both are subjective.

My answer:

This is either question-begging or false, depending on what one means by “flavor”. If all we mean by flavor is how something tastes to someone, then obviously taste is subjective. However, if we pay enough attention to what is meant by “flavor” in the stability condition, it is not difficult to see that, for stability to be a substantial condition, “flavour” cannot be conceived as subjective, and instead we need a more robust notion of flavor. After all, different people find different flavors appealing or disgusting, and here flavor cannot be a subjective property. What does it mean to say that the same flavor X is appealing to some, but disgusting to others? Presumably, it means that everything that is of flavor X (i.e., everything that tastes like X) is appealing to some, but disgusting to others. If flavor was subjective, we would not be able to say this. instead, we would have to say that no flavor can be appealing to some, but disgusting to others, since nothing could have the same flavor to different people. When I say that I find smoky alcoholic beverages tasty, I do not mean that smoky alcoholic beverages have the flavor tasty (to me); instead I mean that the flavor of smoky alcoholic beverages is tasty (to me). In other words, tasty (to me) is not a flavor, but a way of talking of flavors like that of smoky alcoholic beverages.

Still, the subjectivist might insist that flavor just is how stuff tastes, and of course, without someone to taste stuff, stuff would not taste at all. But I find this way of conceiving of flavor is wrongheaded, for it is based on a confusion between what is perceived with how it is perceived. To taste is to perceive flavor, but that does not mean that flavor just pops into existence when it is tasted, i.e.. when it is perceived. Idealism cannot be the default position when talking of perception.

Acknowledgements

This comes from discussing with my friends and colleages Lenny Clapp, Ekain Garmendía, Mario Gómez-Torrente and Carlos Romero.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario